Collection The Decatur House Slave Quarters

In 1821-1822, Susan Decatur requested the construction of a service wing. The first floor featured a large kitchen, dining room,...

Main Content

Abolitionist and White House Valet

How Long? 10 minutes

This article is part of the Slavery in the President’s Neighborhood initiative. Explore the Timeline

President William Henry Harrison’s famously brief month-long tenure at the White House makes it difficult to research the inner workings of the Executive Mansion during his administration, and an 1858 fire at his family’s home in North Bend, Ohio, destroyed many documents related to this particular period of Harrison’s life.1 However, obituaries and recollections reveal a fascinating individual who worked in the Harrison White House: George DeBaptiste, valet to the president and conductor on the Underground Railroad.

George DeBaptiste was a Black man born to free parents George and Jane DeBaptiste circa 1815 in Richmond, Virginia.2 Around 1837-1838, he moved to Madison, Indiana, where he trained as a barber and worked on shipping vessels between Indiana and Ohio; these diverse skills proved advantageous for his future.3 During his time in Madison, he also worked as a station agent or “conductor” with the Underground Railroad, a secret network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom.4 Madison was a key location for these efforts, as the Ohio River separated the slave state of Kentucky from free Indiana.

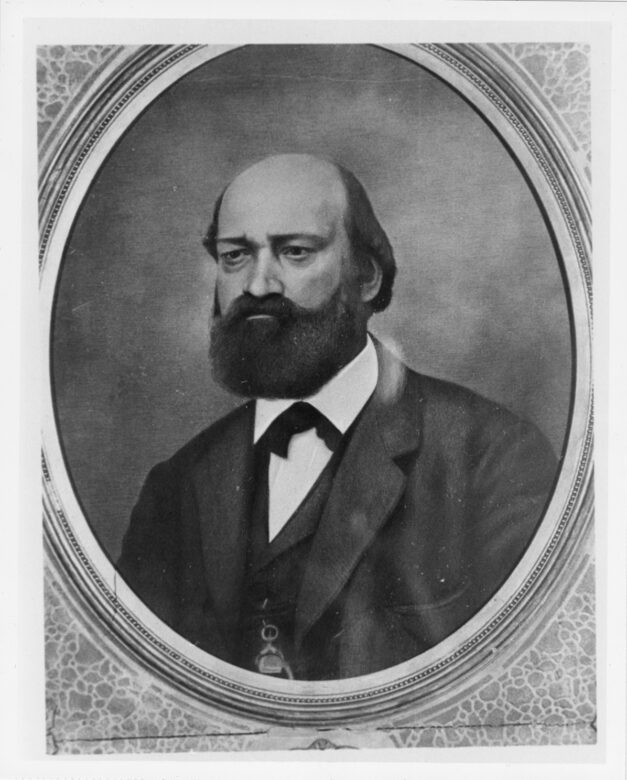

George DeBaptiste

Detroit Public Library, Burton Historical CollectionSoon after, DeBaptiste met General William Henry Harrison—likely through his shipping work on the Ohio River—who hired DeBaptiste to serve as his valet throughout the presidential campaign of 1840; it is unlikely that Harrison knew of DeBaptiste’s abolitionist work.5 Newspapers reported later that “During all this time it was the business of Mr. DeBaptiste to look after the personal wants of the General, who obeyed the behests of his bright and intelligent servant in all matters relating to personal comfort and health.” As valet, he likely shaved and dressed Harrison, and managed his clothing and belongings. DeBaptiste would have also traveled with Harrison while campaigning. An 1875 recollection relayed by “one of [DeBaptiste’s] most intimate friends” described that “Mr. DeBaptiste used to delight in narrating incidents of the campaign of 1840 and he had a fund of anecdote [sic] from which he was wont to draw for the entertainment of his friends on festive occasions.”6

Despite traveling and working closely with a Black man, Whig candidate Harrison was not supportive of abolitionism or African-American rights. Though the Whig Party was divided on the issue of slavery, Harrison’s success relied on his persona as a “Northern man with Southern principles;” his prominence as a military hero known for his campaigns against Native Americans; and the party’s efforts to balance the presidential ticket with southern slave owner John Tyler.7

1840 campaign banner for William Henry Harrison

Library of CongressWilliam Henry Harrison was born into a slave owning family in Virginia. He owned enslaved individuals prior to running for president, and supported states’ rights to make decisions related to slavery.8 While serving as territorial governor of Indiana from 1800-1812, Harrison unsuccessfully petitioned Congress to suspend Article VI of the Northwest Ordinance (1787) which previously prohibited slavery in the region, writing: “the article…which declares that there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in [the territory] has prevented the country from populating and been the reason of driving many valuable citizens possessing slaves to the Spanish side of the Mississippi…”9 Later, he voted with southerners in Congress on the expansion of slavery into U.S. territories and states while representing Ohio in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives.

During the election of 1840, General Harrison’s aversion to abolition became a key talking point. Democrat incumbent Martin Van Buren’s party circulated rumors that Harrison had joined an “abolition society” in Richmond, Virginia, as a young man to sway pro-slavery voters to support Van Buren. Harrison assured his voting base: “You ask me whether I now am, or ever have been, a member of an Abolition society. I answer, decisively, no.”10 Indeed, the abolitionist publication The Liberator noted: “As for ourselves, we are satisfied that Gen. Harrison is as rotten as any slaveholder, in the land, on the subject of slavery, as facts showing this to be the case are daily coming to hand.”11

This 1844 lithograph depicts Harrison’s Inauguration on March 4, 1841.

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionWilliam Henry Harrison defeated incumbent President Martin Van Buren and moved into the White House in March 1841, where George DeBaptiste continued to work as his valet.12 As valet to the president, DeBaptiste likely attended Harrison’s Inauguration on March 4, 1841.13 Little is known about DeBaptiste’s few weeks of work in the White House, but he joined a White House staff which included gardener John Ousley and doorkeeper Martin Renehan.14 Renehan, a longtime White House worker, recollected a conversation with President Harrison in an interview featured in Recollection of Men and Things at Washington. After offering to stoke a fire for the president, Harrison responded: “Martin, when at home I was accustomed to a wood fire; and if I had wood now, I'd replenish this fire myself, as I do not wish to call up my colored man,” probably referencing DeBaptiste.15

President Harrison fell ill just a few weeks into his administration. At the time, physicians attributed his death to pneumonia caused by the cold, wet weather at Inauguration and historians largely accepted this explanation.16 However, recent studies speculate that the cause of death was enteric or typhoid fever caused by poor sanitation in nineteenth-century Washington, D.C. as he fell ill several weeks after Inauguration.17 Several of DeBaptiste’s obituaries mention his presence at Harrison’s deathbed on April 4, 1841, and some went so far as to claim that “President Harrison died in his arms.”18 Though the idea of the two men embracing is likely embellished, it is certainly plausible that DeBaptiste, who oversaw Harrison’s daily health and wellbeing, would have been present as the president’s health declined, especially considering that Harrison’s wife, Anna Tuthill Symmes Harrison, was absent. When Harrison moved to Washington, D.C., she remained in Ohio to recover from her own illness. Nevertheless, newspaper reports and illustrations of Harrison’s final moments from 1841 only include White family, friends, and cabinet members at the president’s side.

1841 artistic rendering of Harrison's deathbed

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionAs the first president to die in office, Harrison’s unexpected passing created several significant presidential precedents.19 His State Funeral took place in the East Room of the White House on April 7, 1841, with black crepe adorning the Executive Mansion.20 Later that day, a procession moved his remains to Congressional Cemetery, where his remains resided in the Public Vault for several months until traveling to North Bend via train.21 George DeBaptiste’s obituary asserted “He… was one of the sincerest mourners at the General's funeral” though evidence again obscures the accuracy of this statement; in fact, the “colored grooms” who guided Harrison’s funeral car are the only African-American participants documented in the funeral proceedings.22

1841 dirge depicting Harrison's funeral procession at the White House

Connecticut College Historic Sheet Music CollectionWhile he worked in the Executive Mansion for the President of the United States, DeBaptiste became well known for another reason: his unfailing dedication to the emancipation of enslaved Americans. Upon President Harrison’s death, DeBaptiste returned to Madison, Indiana, and resumed his abolitionist work, opening a barber shop that served as a stop on the Underground Railroad.23 In these post-White House years, DeBaptiste assisted approximately 180 enslaved people from the bordering slave state of Kentucky in crossing the Ohio River into the free state of Indiana.24 Sometimes, DeBaptiste used his own freedom papers to help enslaved men to freedom; other times, he transported them secretly to their next stop.25 One Indiana abolitionist, John H. Tibbets, recollected:

I received word from George DeBaptiste of Madison, Indiana, that there would be a lot of ten to leave Hunter's Bottom on Sunday night and he wished me to make arrangements to transport them on the underground road that I was acquainted with…We loaded them in, drew down the curtains and started with the cargo of human charges towards the North Star.26

White mob violence erupted in the city of Madison during the 1840s and DeBaptiste soon had a bounty on his head; as a result, he resettled in Detroit, Michigan, in 1846.27

This engraving shows enslaved men, women, and children on the Underground Railroad.

Library of CongressDetroit’s proximity to Canada made it a critical stop on the Underground Railroad—often the last juncture enslaved individuals encountered before crossing into freedom. At this time, slavery was illegal in Michigan, but the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed slave owners to recapture enslaved freedom seekers—even after reaching freedom in states that prohibited the practice.28 Thus, DeBaptiste and his fellow conductors on the Underground Railroad heightened efforts to transport enslaved people to Canada, where the Fugitive Slave Act held no sway.29

Using his experience with steamboats, George DeBaptiste purchased a steamer called the T. Whitney in 1850, which he used to ferry refugees across the Detroit River to Canadian territory.30 Publicly, DeBaptiste worked in a variety of positions including caterer and clerk but in private, he secretly moved men, women, and children out of the United States to freedom, putting his own safety at risk for the sake of others. He did not work alone, as Detroit had a large, active abolitionist community. DeBaptiste helped found the Colored Vigilant Committee of Detroit, a local antislavery organization, with fellow abolitionist William Lambert. He also collaborated with prominent national figures such as Frederick Douglass and John Brown and joined national antislavery groups including the Executive Committee of the National Convention of the Colored Men of America.31

Pencil-drawn map of routes on the Underground Railroad

Library of CongressHis dedication to African-American rights also expanded beyond the immediate pursuit of freedom. DeBaptiste recruited Black soldiers for the Union during the American Civil War and later supported freedmen during Reconstruction.32 In 1870, following the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, DeBaptiste posted a closure note on the door to his building, which was home to the “Office of the Underground Railway.”33 Five years later, newspapers across the country announced the news of his death, caused by stomach cancer, sharing details about his time at the White House and his antislavery heroism.34

Today, President William Henry Harrison’s short tenure in the White House leads many scholars to overlook his administration, including his White House staff, but the relationship between Harrison and his abolitionist valet George DeBaptiste is worth consideration. Did they ever discuss slavery and abolition? It is impossible to know for sure, but the proximity they shared may have influenced their attitudes toward life or politics. Harrison’s untimely death make it hard to conjecture about these conversations, but DeBaptiste went on to have a long, impressive career in antislavery politics that eventually brought freedom to hundreds of enslaved people.

George DeBaptiste’s legacy is celebrated at Detroit’s Gateway to Freedom Memorial, overlooking the Detroit River.

Contemporary Monuments to the Slave PastThis newspaper article from 1888 illuminates the intersection between DeBaptiste’s experiences as a White House valet and advocate for racial equality:

A valuable relic has been received from Detroit by General [Benjamin] Harrison in the shape of the original manuscript of President William Henry Harrison’s inaugural address, being the copy from which he read at his inauguration on the 4th of March, 1841… The 4th of March was a raw, cold day and the President wore a blue cloak for protection against the cold. Before beginning to read his address he removed the cloak and handed it to De Baptiste, who was standing by, to hold. At the conclusion of his address he threw his cloak over him and at the same time handed De Baptiste the manuscript to take care of… the manuscript remained in the possession of De Baptiste.35

DeBaptiste gifted this presidential relic to Colonel Fred Morley to thank him for securing the pardon of an unjustly accused Black man in court. Morley then gave the Inaugural Address to Benjamin Harrison during the presidential election of 1888.36 Harrison went on to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps, winning the election and moving into the White House in 1889.

In 1821-1822, Susan Decatur requested the construction of a service wing. The first floor featured a large kitchen, dining room,...

In 1980, Margaret Johnson Patterson Bartlett, great-granddaughter of First Lady Eliza McCardle Johnson and President Andrew Johnson, gave an oral interview...

Built in 1818-1819, Decatur House was designed by the English architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe for Commodore Stephen Decatur and Susan...

James Buchanan is often regarded as one of the worst presidents in United States history.1 Many historians contend that Buchanan’s...

On February 11, 1829, members of Congress convened to certify votes for President and Vice President of the United States as Andrew...

In 1868, Elizabeth (Lizzy) Hobbs Keckly (also spelled Keckley) published her memoir Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years a Slave, and...

As we consider life in the President’s Neighborhood, the unusual story of the Wormley Hotel and its Black founder, Ja...

In the late eighteenth century, the original thirteen colonies dissolved and formed the United States. In 1787, delegates to the Constitutional...

On April 15, 1848, the Pearl schooner was docked at the wharf located at the foot of Seventh Street in Washington, D....

On April 16, 1862, Congress passed the Compensated Emancipation Act, ending slavery in the District of Columbia and delivering long-awaited freedom to...

January 1, 1863 was a watershed moment in American history. That morning, President Abraham Lincoln hosted the annual New Year’s Day re...

Most Americans do not associate the first ladies with slave ownership. In fact, it may be surprising to learn that...