Collection Native Americans and the White House

Native Americans hold a significant place in White House history. For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples, including the Nacotchtank and...

Main Content

A Complex History

How Long? 11 minutes

President Calvin Coolidge’s relationship with Native Americans is frequently summarized by a passing reference to his signing of the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, if it is mentioned at all.1 While Coolidge’s support of the legislation is unquestioned, reducing his many interactions with Native Americans to a single piece of legislation is misleading and inaccurate.

Coolidge’s interest in Native Americans was not only political but also personal. Coolidge claimed he was descended from Native Americans, alleging in his published autobiography that his father’s side of the family included a “marked trace of Indian blood.”2 Possibly influenced by this belief, Coolidge actively engaged with Native Americans as president and promoted these interactions in the media. Coolidge hosted Native Americans at the White House numerous times, publicly released posed photographs with them, and even visited a Native American tribal reservation in South Dakota. Coolidge also gave his assent to the national monument construction of Mount Rushmore, which exists on federal land confiscated from the Lakota Sioux, the original occupants of the Black Hills in South Dakota. Coolidge’s relationship with Native Americans is complex and multi-faceted, although largely driven by his belief that Indigenous peoples must assimilate into U.S. culture and that the federal government should promote such efforts.3

Calvin Coolidge is joined at the White House by Ruth Muskrat and the Committee of One Hundred on December 13, 1923.

Library of CongressIn 1923, President Coolidge met with members of the Committee of One Hundred, formally titled the Advisory Council on Indian Affairs. This group had been created earlier in the year by Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work, who served under the previous administration of President Warren Harding and continued under Coolidge. In addition to creating the advisory Committee of One Hundred, Work reorganized the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the principal federal government agency responsible for treaty negotiations and implementing policies affecting Native Americans.4 Coolidge was aware of Work’s efforts, which likely led to the invitation for members of the Committee of One Hundred to visit the White House on December 13, 1923.

The Committee of One Hundred consisted of scholars, activists, and policy specialists (both Native American and non-Native American) who advised the federal government on critical issues facing Indigenous peoples. During the White House visit, a young Native American poet and Mount Holyoke junior named Ruth Muskrat addressed President Coolidge and presented him with a copy of The Red Man in the United States, a book describing the adverse economic, educational, religious, and cultural challenges facing Native Americans. In her speech, she spoke frankly to President Coolidge, beginning with this pointed question that framed her speech:

Mr. President, there have been so many discussions of the so-called Indian Problem. May not we, who are the Indian students of America, who must face the burden of that problem, say to you what it means to us?

Muskrat continued her speech, providing an answer her own question:

The old life has gone. A new trail must be found, for the old is not good to travel farther. We are glad to have it so. But these younger leaders who must guide their people along new and untried paths have perhaps a harder task before them than the fight for freedom our older leaders made. Ours must be the problem of leading this vigorous and by no means dying race of people back to their rightful heritage of nobility and greatness. Ours must be the task of leading through these difficult stages of transition into economic independence, into a more adequate expression of their art, and into an awakened spiritual vigor… We want to become citizens of the United States, and to have our share in the building of this great nation, that we love. But we want also to preserve the best that is in our own civilization.5

President Coolidge and First Lady Grace Coolidge were moved by Muskrat’s poignant words and subsequently invited her to dine with them at the White House for lunch. The New York Times described the delivery of her speech as exhibiting “force and clarity.”6

The December 1923 Native American visit to the White House and Ruth Muskrat’s speech may have influenced Coolidge to support and sign the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act on June 2. He was also likely inspired by the recent military service of thousands of Native Americans in World War I.7 Originally, the drafted legislation would have required Native Americans to apply for citizenship. An amendment in the Senate changed this provision to an automatic conferral of citizenship to all Native Americans who were not already citizens.8 Since the Fourteenth Amendment’s ratification in 1868, pockets of the Native American population had been granted citizenship, such as Native American women who married citizens and those who, under the 1887 Dawes Act, had “moved away from tribes” and adopted the so-called “habits of civilized life.”9 In 1924, 125,000 of the approximately 300,000 Native Americans in the United States remained non-citizens. The Indian Citizenship Act granted United States citizenship to this remaining group of Indigenous people.10

Although the 1924 legislation conferred citizenship on all Native Americans born within the territorial borders of the United States, voting rights for Native Americans remained contested. Even after the enactment of the 1924 legislation, many Native American populations were denied suffrage, frequently subjected to state-imposed poll taxes and literacy tests. In this sense, Native Americans were treated as “second-class citizens,” much like African Americans and Chinese Americans at that time.11 It was not until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that all Native Americans could exercise the right to vote in any state or territory in the United States.12 While the conferral of citizenship upon all Native Americans was viewed as a liberalizing action by proponents of the legislation, some Indigenous people did not consider it desirable. Certain nations denounced the Indian Citizenship Act, arguing that the “imposition of citizenship” effectively “contradicts the sovereign status of Native nationhood and membership within it.”13 Some tribes and Native Americans viewed the Indian Citizenship Act as promoting assimilation and reducing tribal independence.14 For example, the Onondaga Nation sent President Coolidge a letter on December 30, 1924, outlining their opposition to the law.15

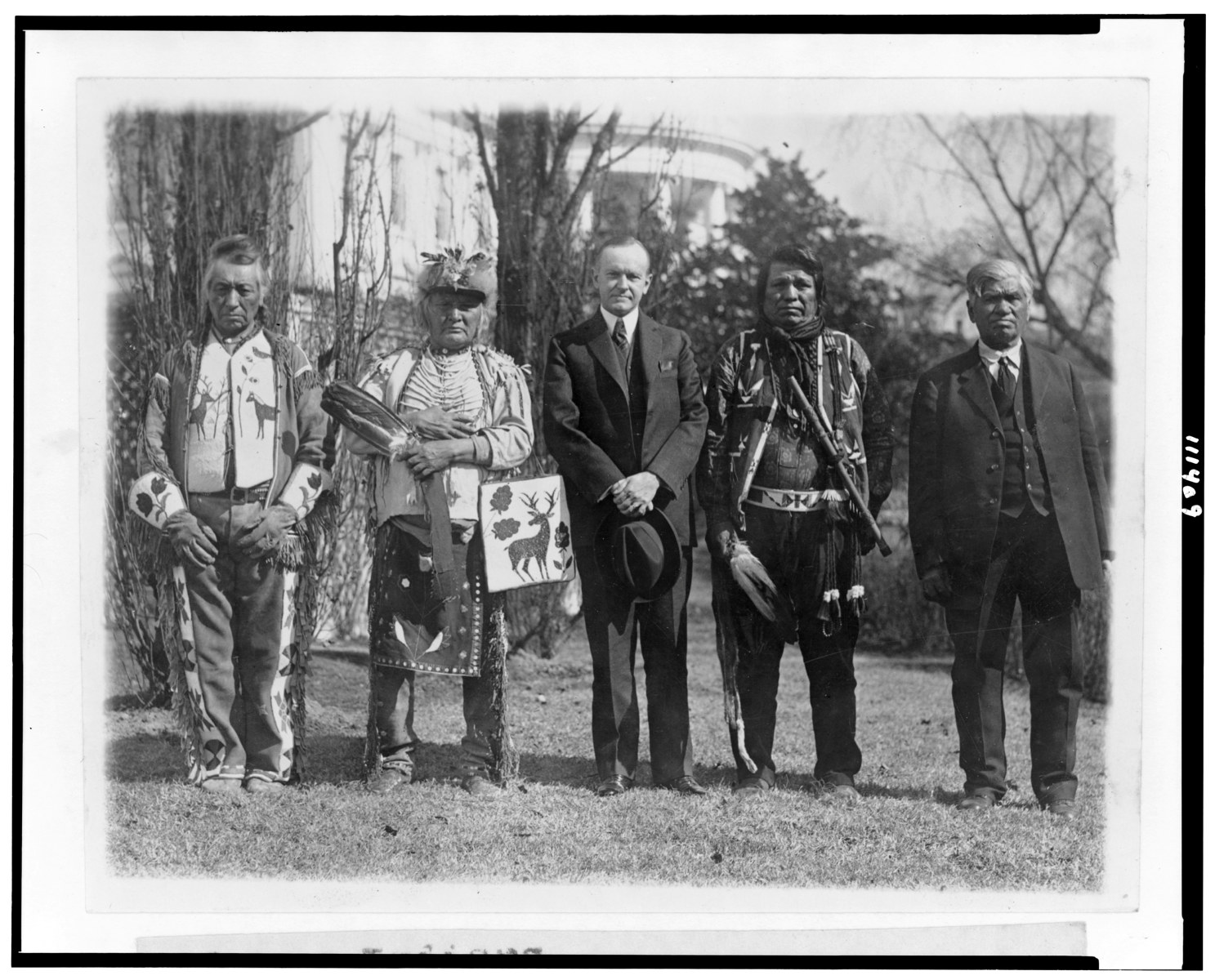

Calvin Coolidge meets with Native Americans from the Plateau region of the United States in 1925.

Library of CongressTo commemorate the enactment of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, President Coolidge hosted several delegations of Native Americans at the White House in 1925. On February 18, 1925, Coolidge hosted a Native American delegation from the Plateau region of the northwestern United States.16 Less than a month later, on March 10, 1925, Coolidge received over twenty Native Americans, including three Sioux chiefs who were descendants of Sitting Bull.17 On May 6, another group of Sioux visited the White House. After watching them assemble for a photograph on the South Lawn, President Coolidge reportedly asked if he could pose with them.18 Coolidge was the last president to rely upon newspaper coverage as his primary method of communication with the American public.19 By inviting several Native American delegations to the White House and ensuring he was photographed with them, Coolidge successfully signaled his support of Native American citizenship and acknowledged the changing landscape of the nation’s pluralism. The numerous photographs at the White House were likely an attempt to confer civic legitimacy upon Native Americans but were considered by some as promoting policies of assimilation.

In 1926, Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work commissioned a study from the Institute for Government Research (now the Brookings Institution) to analyze the social and economic conditions of American Indians living on reservations. The report, led by Lewis Meriam, was issued on February 21, 1928. It was formally titled “The Problem of Indian Administration” but became known as the “Meriam Report.”20 The 847-page report included sections on many subjects, including health, the roles of Indigenous women, family life, and economic opportunity. The Meriam Report criticized the Dawes Act of 1887, which relocated Native Americans from their lands to allotments provided by the federal government. Although the Meriam Report was issued during the end of the Coolidge administration, its findings did not systematically affect Native American policy until the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, when the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act was passed.

Calvin Coolidge meets with members of the Sioux Indian Republican Club of the Rosebud Reservation at the White House on March 10, 1925.

Library of CongressIn 1927, the Coolidge family vacationed in South Dakota for several months, living at the State Game Lodge in Custer State Park that served as the “Summer White House.” In July and August, Coolidge met with tribal leaders at a variety of locations, including at the State Game Lodge and at an off-reservation Native American boarding school.21 On August 4, 1927, representatives from the Lakota appeared with President Coolidge and First Lady Grace Coolidge at Deadwood, a historic mining town. Henry Standing Bear addressed Coolidge during this meeting, along with Chauncey Yellow Robe and his daughter, Rosebud. The press coverage of Rosebud presenting Coolidge with a feather bonnet and yellow skins was extensive, and eventually helped her to launch a public career when she subsequently left South Dakota for New York City.22 After the remarks by Standing Bear, Chauncey bestowed the Lakota name Wanblee-Tokaha, or “Leading Eagle,” upon President Coolidge and Rosebud placed the bonnet on Coolidge’s head. Mrs. Coolidge was also presented with moccasins.23 The ceremony was photographed, and the images were shared widely, with one appearing on a postcard.24 Press coverage of the induction was found on the front page of leading newspapers such as the New York Times, Baltimore Sun, and Los Angeles Times.25

Calvin Coolidge on vacation in Black Hills, South Dakota in 1927.

Library of CongressAfter his induction to the Lakota tribe on August 4, 1927, Coolidge attended the dedication of the Mount Rushmore site in the Black Hills, located on Lakota Sioux land that the federal government had seized from Indigenous people.26 When gold was discovered in the Black Hills in 1874, the federal government reversed the earlier 1868 Treaty of Laramie, which reserved the land for the Sioux. Despite his recent interactions with local tribes, Coolidge’s speech at Mount Rushmore did not mention Native Americans or the contested land, although he did concede that “probably no white man had ever beheld” this sight during the days of George Washington.27

On August 17, 1927, President Coolidge traveled to the southwestern corner of South Dakota to visit a Lakota tribal reservation called Pine Ridge, located in the Black Hills. Lakota leaders understood the significance of the event, as this was the first time in history that a sitting President of the United States visited a Native American reservation. An elder of the tribe, Black Horn, greeted President Coolidge and began a processional that included five hundred Lakota who sang, danced, and played the drums. During the visit, Sioux National Council tribal leaders asked Coolidge to assist with their disputed land claim concerning the Black Hills. Coolidge addressed the Lakotas and spoke of the Indian Citizenship Act and other policies geared at assimilation, such as land allotment, boarding schools, and English literacy. Coolidge also publicly criticized Native American policy, describing its administration as convoluted and problematic due to often contradictory federal laws, state laws, treaties, decisions, and court cases, and regulations. According to Coolidge, the situation ultimately resulted in “injustice to the Indians.”28 He did not address the issue of disputed land in his speech.29 This issue remains unresolved today, despite the Supreme Court ruling (8-1) in favor of the Sioux Nation in 1980. Due to a desire to have the land returned to them, the Sioux have refused the awarded monetary compensation, which now totals close to two billion dollars with accrued interest.30

President Coolidge speaks at the dedication of the Mount Rushmore Memorial on August 10, 1927.

U.S. National Parks Service, Charles D'EmeryThroughout his presidency, Coolidge demonstrated an “unusual interest” in Native American affairs but not all his activity was welcomed by Native Americans.31 While he sympathized with the plight of Native Americans and the difficulties they faced, Coolidge maintained federal policies focused on assimilation and prevented Native Americans from submitting land claims, vetoing bills repeatedly that would have provided legal standing to tribes aiming to sue for land reparations.32 Given the number of times Native American delegations visited the White House and his own trip to the reservation in Pine Ridge, Coolidge clearly promoted his interactions with Native American populations and viewed them as helpful to his public persona.

Coolidge understood that the media landscape was changing, and the American presidency was rapidly becoming an office heavily reliant upon a cultivated image and press coverage.33 Although Coolidge’s astute self-awareness about the evolving demands of the presidency provided prescient, many of his beliefs about Native Americans were firmly grounded in the previous century’s predominant paternalistic policies of assimilation. In that sense, Calvin Coolidge’s relationship with Native Americans might be described as dipping one foot in modernity with the other firmly planted in the traditional views of the past.

Native Americans hold a significant place in White House history. For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples, including the Nacotchtank and...

Geography, history, and friendship have been the driving force of ties between the United States and Canada. In 1927, official rapport...

Presidents have found different ways to escape the pressures and politics of the position. For early leaders, it was a...

Biographies & Portraits

The White House observance of Christmas before the twentieth century was not an official event. First families decorated the house...

Death comes to every home, including the White House. From the loss of cherished family members to presidential funerals, there...

No sport is more closely tied to the American presidency than baseball. One of Washington’s first baseball fields was lo...

The origin of the "American Presidents" by Genevieve Ryan Bellaire is somewhat unique. One year, Genevieve's father asked her to...

As part of the White House Historical Association’s 60th anniversary celebration in 2021, the Next-Gen Leaders (NGL) initiative was announced. Th...

Congress has always been tasked with appropriating funds for the care, repair, refurnishing and maintenance of the White House and...

NUMBERS 1 THROUGH 6 (COLLECTION I) WHITE HOUSE HISTORY • NUMBER 1 1 — Foreword by Melvin M. Payne 5 — President Kennedy’s Rose Garden by Rachel Lambert...

Since joining the White House Historical Association in 2014, Stewart McLaurin has had been published a number of times. Topics range...